| |

What is this "song-poem"?

by Phil Milstein

[The short answer]

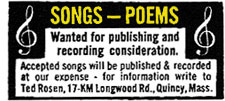

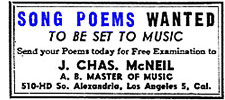

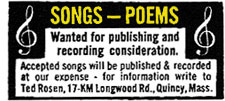

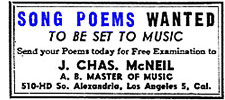

"SONG-POEMS WANTED," blare small, noisy display ads buried in the human misery ghetto -- amid similar notices for rupture trusses, depilatory devices and bust-enlargement creams -- at the back of pulpy, mass-market magazines. "WE NEED NEW IDEAS FOR RECORDING."

It sounds intriguing, but you're not sure what to make of that cryptic lead-in phrase: song-poem. It's not found in any dictionary. While it might seem to simply imply "poetry set to a tune," what "song-poem" actually refers to is something more specific than that -- something, in fact, that has much more to do with commerce than it does with songs, poetry or music.

The song-poem story involves a succession of publishing and recording companies that have occupied the lowest rungs of the music industry ladder for over 100 years. By appropriating the rhetoric of the legitimate (so-called) music industry, the owners of such companies prey on the dual yearnings among the general public for access to the inner sanctum of show business and a means to get rich quick, as well as the fact that nearly everyone has written some sort of poem at one point in their life or another. Song-poem entrepreneurs (called "song sharks") manipulate these facets of human nature to deceive naïve individuals into subsidizing a quest to have their poem become the lyric of a smash hit record. In the parlance of this parallel-universe enterprise, "song-poem" is code for the originating verse. The reason that a code is resorted to bespeaks of the patronizing nature of the song-poem game: its proprietors believe that their typical customer is too dumb to grasp the meaning of the simple English word "lyric." At the same time it's meant to signal an expanse of possible source materials, as in, "We'll set your song, your poem, even your goddamn shopping list to music; we don't care what you give us, so long as your checks don't bounce."

| |

|

|

|

Series of deceptions

The song-poem process begins with those enticing little ads, placed by song sharks in any publication for which they perceive a large and credulous readership: movie mags, comic books, supermarket tabloids, even such relatively specialized journals as Popular Mechanics. Running these ads is like dropping a baited hook into a well-stocked lake. When the song-poet responds by sending her (for most song-poets are female) verse in for "evaluation," the shark mails back a barrage of promotional literature in which he (for most song sharks are male) lays out a more sophisticated round of deceptions than can be squeezed into the ads. The verse, no matter how hopeless, is invariably given a top rating, thus inflating the song-poet's ego and expectations. When such puffery is supplemented with anecdotes of just how much money there is to be made in songwriting, and hints of how "anything can happen" and "you never know," the fish starts to nibble at the bait.

The next twist is perhaps the trickiest of all, for even the dumbest perch in the pond knows that in the music industry, if you've got a salable commodity then companies will pay you for access to it. Instead, the song-poem company must convince the song-poet that she should pay them, typically to the tune of $200 to $400. To pull this off the company must resort to a mechanism borrowed from the evangelism industry, an industry with which, helpfully, many song-poets are already familiar. The company suggests that its fee constitutes merely the "seed money" required before it can begin to develop the lyric into a finished record, and represents but a small portion of the total costs involved. In fact the fee -- or so claims the literature -- is levied not so much for the revenue it will bring the company but rather as a "show of good faith," a demonstration that the song-poet believes strongly enough in the quality and potential of her handiwork to deem it worthy of financial risk. The truth, of course, is that the fee covers a lot more than just a "small portion" of the costs: it subsidizes the entire overhead and profit for that record, and so once the record is produced and manufactured the company has already gotten from it everything that it can. It is of no further value to them.

But no record can succeed without the post-pressing functions of promotion and distribution. Indeed, song-poem literature suggests that the company will undertake an active P&D campaign in support of the record. But song-poem executives are keenly aware that such costly services are in reality best invested in records that someone might actually want to spend money to listen to, and equally aware that song-poem records are anything but that. Therefore, and in spite of all claims to the contrary, in the song-poem game promotion and distribution are usually dispensed with altogether. Given this fact, the closest thing to a "release" most song-poem records actually receive is when a batch of them is mailed to the song-poet.

Once these hints, lies and half-truths have successfully persuaded the fish to chomp down, the shark can now reel 'er in. As soon as the cash is fully transacted (which can takes months, as layaway plans are a staple of the song-poem game), the back end of the process kicks in: the factory assembly-line of music. The lyric is placed on a conveyor belt, where its first stop is the melody desk. There, in a crude simulation of a genuine songwriting collaboration, a staff composer quickly plunks out a rickety tune. The completed song is then sent to an airless studio, where musicians, vocalists and an engineer gather to record it and many others like it as fast as is humanly possible, often on a quota basis that can gobble up 12 or more songs per hour. Finally the tape is sent to the manufacturing plant, where a record, cassette or CD is fabricated from it, sometimes in the form of a single, with just one or two songs, while other times, in the song-poem equivalent of a mass grave, as an album with 15 to 20. Some or all of the finished product is then returned to the customer, thus fulfilling the company's bottom-line obligation. Having nothing left to gain from it, the company ignores all future consideration of the record, preferring to invest its efforts in the pursuit of fresh victims. Meanwhile, the song-poet is left holding a stack of records not even her family truly cares to hear.

Once these hints, lies and half-truths have successfully persuaded the fish to chomp down, the shark can now reel 'er in. As soon as the cash is fully transacted (which can takes months, as layaway plans are a staple of the song-poem game), the back end of the process kicks in: the factory assembly-line of music. The lyric is placed on a conveyor belt, where its first stop is the melody desk. There, in a crude simulation of a genuine songwriting collaboration, a staff composer quickly plunks out a rickety tune. The completed song is then sent to an airless studio, where musicians, vocalists and an engineer gather to record it and many others like it as fast as is humanly possible, often on a quota basis that can gobble up 12 or more songs per hour. Finally the tape is sent to the manufacturing plant, where a record, cassette or CD is fabricated from it, sometimes in the form of a single, with just one or two songs, while other times, in the song-poem equivalent of a mass grave, as an album with 15 to 20. Some or all of the finished product is then returned to the customer, thus fulfilling the company's bottom-line obligation. Having nothing left to gain from it, the company ignores all future consideration of the record, preferring to invest its efforts in the pursuit of fresh victims. Meanwhile, the song-poet is left holding a stack of records not even her family truly cares to hear.

The good ones

But if song-poem records are so worthless, so debased, so utterly forsaken, then what is it about them that provides such delight to the genre's legions of fans? In what way do these records rise above their tarnished origins as the products of such a debauched process? The fact remains that most song-poem records are dreary endeavors bereft of all artistic merit, and offer only the most strenuous of listening experiences. But while those that are worth a second spin may be proportionally small, the song-poem industry has pumped out such a vast pile of product over the decades that the good ones that have so far been located total well into the hundreds, with the list steadily expanding.

Among the unique pleasures the good ones have to offer are:

the complex interactions at play between pro and am; cynicism and naïvete; talent stunted and craftlessness given wing;

the dearth of quality control so inconceivable that the fact the record was made at all is manifestly bewildering;

the effervescent kick of a period-piece peek at a passing whim of pop culture;

the many oblique relationships between song-poem music and "real" music;

the utter wrongness of the manner in which problems often are solved, solutions which in other hands would be the problems;

the unrefracted view of sincere human emotion which, though often morose, is also at times genuinely poignant, and is always a refreshing contrast to the calculated and condescending product that dominates our culture;

the fact that because the bankroller is ignorant of the rules of record-making, those rules are always subject to variation or outright abandonment;

the sheer ludicrousness of so many aspects of so much of the finished product;

the element of surprise, in that even the most innocuous-looking song-poem record, when played, may well reveal the most unexpected details;

the fact that in the song-poem game, every deceptive transaction ultimately produces a unique work of art;

and, most happily of all, the occurrence of that very rare song-poem record which supercedes all expectations by being excellent by any standard.

Where we come in

Because most song-poem companies provide a checklist of pop music styles from which the customer may select a favorite or most suitable mode for their song to be set in, the studio personnel assigned to make the record does so according to a readymade template that roughly resembles that style. But, given the circumstances under which they work, what emerges tends to be closer to a stylistic parody than an authentic interpretation, a twist which plays right into the hands of song-poem music's jaded, postmodern audience.

But if the appreciation of song-poem music were informed by irony alone, the genre would be rightly dismissable as fodder for cheap yuks at the expense of people who simply don't know any better. That it may be, but the saving grace is that it is also much more than that, and most song-poem collectors fully appreciate the many nuances involved. These fanatics are happy to scour through thrift store dust and swap meet grime to unearth their rare finds. They then funnel news of them to the American Song-Poem Music Archives, where their reports of long-lost record labels and long-deceased song-poets are taken down and spun into the presentation at hand. We urge any song-poem collectors whose holdings are not currently accounted for to send us details of them.

In addition to compiling the AS/PMA discographies, we venture to trace the history of this wondrous and heretofore neglected corner of our culture. Throughout these pages you will find from passing references to complete tales of many of the song-poem companies, performers, entrepreneurs and the song-poets themselves. We readily acknowledge that the work we've done so far, as extensive as it is, represents just a fraction of the complete record of the song-poem music genre. We therefore invite anyone with experience in any capacity of the song-poem industry -- whether as customer, composer, engineer, singer, musician, office staff or company owner -- to send in their own stories.

Perhaps our most popular feature is the MP3 collection, where we offer, free for the downloading, hundreds of MP3 files of complete, top-notch song-poem recordings. Our special pet, however, is the Shadow World section, where we present research, most of it illustrated, on some of the more ancient and arcane artifacts of song-poem lore.

Rodd is godd

Rodd is godd

Surpassing all other virtues of song-poem music are the recordings of the late, great auteur Rodd Keith. A gifted and versatile musician, Rodd's career encompassed virtually all phases of song-poem studio work, including composition, instrumentation (primarily keyboards), arrangement, production, and lead and harmony singing. Where other song-poem studio performers have ranged from hack to craftsman, and a handful have even been worthy of the dubious honor of artist, Rodd was unequivocally a genius. Not all of his recordings were gems, but the scads of those to which he applied himself (often under a sub-alias, i.e. Rod Rogers, Cleveland Becker, Ron Davis, Dean Curtis, John Dough, Lindon Bridges, Rood Keith, et al) can stand with the finest works of any genre.

The success of Rodd's performances provokes a question that applies equally to all other quality song-poem records: why bother? Why would the studio hands exert any effort towards making a worthwhile record of a song that will likely be heard by just one person? The answer remains elusive, but a few possibilities come to mind. There exists, of course, the basic capitalist conceit of trying to please a paying customer in order to secure his or her repeat business; yet, judging by the results, in the song-poem sweatshops that notion appears to have been given little consideration. There is also the factor of personal pride, but in the song-poem game, where expediency is all and the operative adjective is "threadbare," pride is a luxury company executives ill tolerate.

Perhaps the answer lies instead with the boredom factor. To have to act inspired by a succession of ditties about lost loves, sainted mothers, war efforts, doomed celebrities and beloved pets can be a most oppressive way for a singer to earn a living. Under such stifling conditions he grows desperate -- at times, even crazy -- waiting for the one song in ten (to apply a generous estimate) that might afford him the opportunity to rouse his talents. Of his tedium thus comes a kind of elevation. From such moments have been compiled several anthology albums of the very best song-poem recordings, with several more in the pipeline.

All design and uncredited content of this website ©2003 Phil Milstein

Once these hints, lies and half-truths have successfully persuaded the fish to chomp down, the shark can now reel 'er in. As soon as the cash is fully transacted (which can takes months, as layaway plans are a staple of the song-poem game), the back end of the process kicks in: the factory assembly-line of music. The lyric is placed on a conveyor belt, where its first stop is the melody desk. There, in a crude simulation of a genuine songwriting collaboration, a staff composer quickly plunks out a rickety tune. The completed song is then sent to an airless studio, where musicians, vocalists and an engineer gather to record it and many others like it as fast as is humanly possible, often on a quota basis that can gobble up 12 or more songs per hour. Finally the tape is sent to the manufacturing plant, where a record, cassette or CD is fabricated from it, sometimes in the form of a single, with just one or two songs, while other times, in the song-poem equivalent of a mass grave, as an album with 15 to 20. Some or all of the finished product is then returned to the customer, thus fulfilling the company's bottom-line obligation. Having nothing left to gain from it, the company ignores all future consideration of the record, preferring to invest its efforts in the pursuit of fresh victims. Meanwhile, the song-poet is left holding a stack of records not even her family truly cares to hear.

Once these hints, lies and half-truths have successfully persuaded the fish to chomp down, the shark can now reel 'er in. As soon as the cash is fully transacted (which can takes months, as layaway plans are a staple of the song-poem game), the back end of the process kicks in: the factory assembly-line of music. The lyric is placed on a conveyor belt, where its first stop is the melody desk. There, in a crude simulation of a genuine songwriting collaboration, a staff composer quickly plunks out a rickety tune. The completed song is then sent to an airless studio, where musicians, vocalists and an engineer gather to record it and many others like it as fast as is humanly possible, often on a quota basis that can gobble up 12 or more songs per hour. Finally the tape is sent to the manufacturing plant, where a record, cassette or CD is fabricated from it, sometimes in the form of a single, with just one or two songs, while other times, in the song-poem equivalent of a mass grave, as an album with 15 to 20. Some or all of the finished product is then returned to the customer, thus fulfilling the company's bottom-line obligation. Having nothing left to gain from it, the company ignores all future consideration of the record, preferring to invest its efforts in the pursuit of fresh victims. Meanwhile, the song-poet is left holding a stack of records not even her family truly cares to hear. Rodd is godd

Rodd is godd